There are many animals that reproduce asexually – stick insects, fish, armadillos, frogs, lizards – the list could go on. When it comes to weird ways to do this, though, Aeolosoma takes the cake.

Aeolosoma is a genus of tiny, transparent worms from the class Oligochaeta, which includes earthworms and other segmented worms. They are almost exclusively aquatic and range in length from 1-10 millimeters. These oligochaetes feed on vegetation and water scum, as well as any small organisms unfortunate enough to get hoovered in with the current produced by their mouth cilia. This is all pretty typical for aquatic annelids, except when they start reproducing like a horror movie monster.

When a worm is mature, its last segment (the pygidial segment) starts to become a completely separate worm through the development of what is called a pygidial bud. Once that worm has grown all its segments, it too forms a new worm from its dividing pygidium. This continues until a chain of 2-6 worms is formed, at which point the chain divides in half and the process continues. Each of these developing worms is referred to as a zoid (plural: zooids). How does the worm behind another worm live, you ask? Well, it’s almost exactly like that disgusting movie The Human Centipede, only with worms. All of the zooids are connected through their circulatory and digestive systems and move in a coordinated way. Only when a worm is about to separate does it show independent muscle movement and only the last segment shows this.

Nightmare reproduction!

Researchers Fred Kamemoto and Clarence Goodnight looked at the effects on Aeolosoma reproduction of different concentrations of calcium, potassium, and magnesium ions at varying temperatures. After a lot of time and a lot of worms, they concluded that there is a very complex interaction between the ions that makes it difficult for the effect of one to be singled out from any other. However, they generally found higher concentrations of calcium to be stimulating at most temperatures and higher potassium concentrations to have a toxic effect. At 10ºC, no reproduction occurred and the worms remained in a dormant state throughout the experiment. In other words, some like it hot, including these worms.

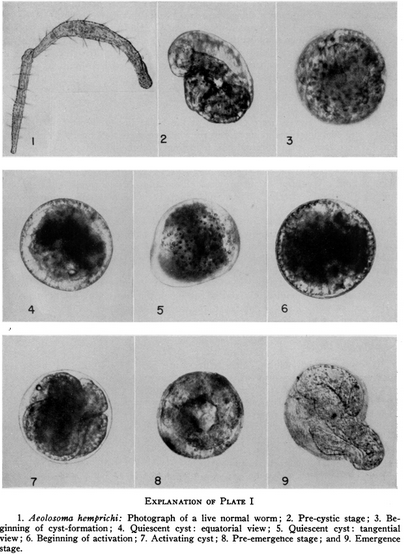

Other studies have also been done on how these little worms cope with temperature, such as Henriette Herlant-Meewis’ research on cyst formation. Cyst formation in Aeolosoma hemprichi is a process in which the worm secretes a protective mucus that hardens and encloses it in a shell-like sphere. It was first discovered in 1905 when the worms were exposed to cold, winter temperatures. Herlant-Meewis experimented with temperatures from at 3ºC, 6ºC, and 11ºC and observed their responses. Cysts did not form in worms subjected to an 11ºC environment, but many cysts were seen after 30 days in 3ºC and 6ºC medium. She took her study a step further after these observations and decided to throw food supply into the mix of cyst formation limitations.

Aeolosoma were removed from their cozy, 18ºC stock culture full of nutrients and placed in pure water at 3ºC and 6ºC. By 15 days, all worms were either dead or dying and no cysts or pre-cysts stages were found. She followed up by taking 250 healthy worms living in 6ºC medium with plenty of nutrients and separated them into two groups once they had reached the pre-cystic stage. One group was placed in the same conditions as they were taken from, and the other group was subjected to pure water with no food. After seven days, Aeolosoma in the first group began to form cysts, while those in the second group died and did not form cysts.

Her conclusions were that the worms need plenty of food to store as a reserve when they enter a cyst stage. It is like a form of hibernation. If there is not a sufficient food source, they will not have the energy to form a cyst to protect themselves from the cold and will die in consequence. This is suspected to occur in the winter when water temperatures drop. Worms will feed voraciously to stock up before they form cysts and fall to the bottom of their pond or pool. Here, they can endure in warmer pockets that stay above freezing and emerge in spring as temperatures warm.

Aeolosoma worms may be small and simple creatures, but many a researcher has been smitten with their curious ways, striving to understand everything they possibly can about them. This just goes to show that even the most seemingly boring and nondescript organisms can tell us the most amazing stories about their lives if we just take the time to observe and learn.

References:

1. Kamemoto, Fred I., and Goodnight, Clarence J. “The effects of various concentrations of ions on the asexual reproduction of the oligochaete Aeolosoma hemprichi.” Transactions of the American Microscopical Society (1956): 219-228.

2. Falconi, Rosanna, Tommaso Renzulli, and Francesco Zaccanti. “Survival and reproduction in Aeolosoma viride (Annelida, Aphanoneura).” Hydrobiologia 564.1 (2006): 95-99.

3. Herlant-Meewis, Henriette. “Cyst-Formation in Aeolosoma Hemprichi (Ehr).” Biological Bulletin (1950): 173-180.

Photo Links:

1.http://www.naturamediterraneo.com/forum/topic.asp?TOPIC_ID=206115

2.http://animalkingdom.su/books/item/f00/s00/z0000048/pic/000323.jpg

3.http://www.jstor.org/stable/1538737?seq=3#page_scan_tab_contents